“So you’re a languages teacher? I learned French at school, but I can’t say a word now…”

If I had a pound for every time I’ve heard someone say that, I’d be, well, quite rich indeed. According to the British Council, two in three Britons are unable to hold a conversation in a language other than their mother tongue, and the lack of language skills in the UK workforce is detrimental to the UK’s strategic and economic interests. The lack of language skills within the UK workforce is estimated to cost the UK 3.5 % of GDP per year.

If you are someone who had the opportunity to learn a language at school, you are part of a dwindling group in the UK. Recent trends in languages learning in UK school is alarming, with French and German entries at GCSE declining year on year. This decline means that fewer Britons will have the intercultural insight and knowledge that comes with learning a language, as well as being less literate than their counterparts in other countries who speak two more languages. For anyone who cares about how our young people’s ability to navigate a complex world or to engage with difference, this is a worrying trend.

In Scotland we are fortunate to have a vibrant ecosystem of passionate teachers, academics and various other organisations who go to great lengths to promote the uptake of languages in our schools. I’m thinking of the Scottish Association of Language Teachers (SALT), SCILT Scotland’s National Centre for Languages, our excellent universities, the various government consolates and cultural institutes such as the Goethe Institut and the Institut Français, to name just a few.

The enthusiasm and drive to boost language learning are clearly there. But I can’t help but feel that what we offer our young people in the classroom falls short of our aspirations. What and how our students are learning is arguably the most important factor in how motivated they will be to learn another language, yet it’s also one of the most difficult things to change. Education systems are complex and are deeply entwined with and constrained by the values of a society, deeply held teacher beliefs, traditions and organisational structures. For the busy teacher (and let’s not forget that Scottish teachers are amongst the busiest in the developed world), day to day survival is paramount. It’s difficult to find the time or energy to stand back and actually think deeply about our practice, let alone make the changes we know are necessary.

In my quest for inspiration, I stumbled across Dr Liam Printer’s podcast for languages teachers, The Motivated Classrooma few years ago. Liam is a teacher of Spanish and English at the International School of Lausanne in Switzerland and completed a doctorate focused on the motivational impact of teaching languages through input-driven activities such as co-created storytelling. His podcast is a treasure trove of insight into the research around languages acquisition (SLA) and motivation in languages learning, and provides loads of practical tips for languages lessons.

Liam’s podcast led me to south-west France, where I started attending The Agen Workshop, an international conference that brings together teachers from all over the world to learn about and explore comprenhension-based approaches to language teaching. I met many inspiring languages teachers who had one thing in common: a desire to teach languages in a way that is inspiring and that motivates learners to develop the ability to communicate effectively.

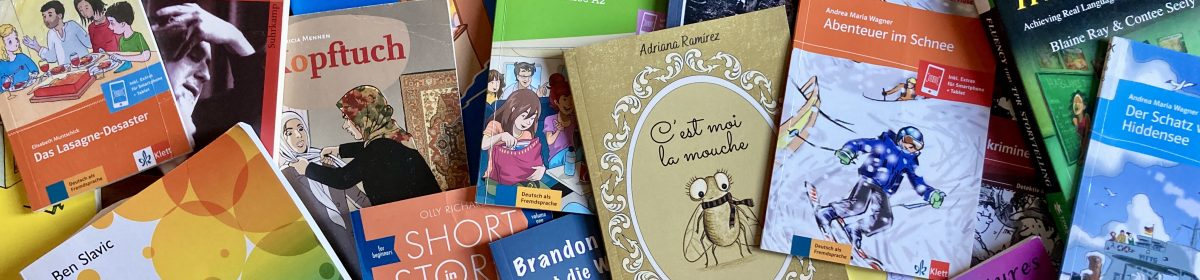

Subsequently, I was awarded a Churchill Fellowship to undertake a research project in languages teaching and pedagogy. As part of this Fellowship I’ll be spending time observing teaching and learning in four secondary schools in Canada, Switzerland and Germany. In all of these schools I’ll be observing teachers who are using comprehension-based strategies in their teaching. Comprehension-based teaching (sometimes called CI – Comprehensible Input – teaching) draws on the research of SLA scholars such as Stephen Krashen and Bill Van Patten who argue that we learn language primarily by understanding messages we hear and read (“comprehensible input”). Rather than starting with explicit grammar instruction, the teacher might use stories and narrative as a way to increase the amount of input learners receive. Co-created stories, “story listening”, graded readers and extensive free voluntary reading are some more examples of strategies comprehension-based teachers may use.

I’m seriously excited to have the opportunity to learn from other teachers in a number of different contexts… I leave for Vancouver on 27th April 2024, before continuing my journey to Lausanne in May, followed by Frankfurt am Main in June. I’ll be blogging about what I learn along the way and hope to offer some insights into what languages teaching looks like in some very different education systems from Scotland and the UK. I hope this may be of interest to other languages teachers in Scotland, the rest of the UK and beyond.

I don’t think there’s a Holy Grail when it comes to languages pedagogy and curriculum. But I know that we can and must continue to develop and refine what we offer our young people, in order that as many of our students as possible discover the joy and satisfaction of learning another language. As I embark on this learning journey, please do join me along the way and feel free to leave a comment!